What are introductory phrases? An introductory phrase starts off a sentence. But did you know there isn’t just one type of introductory phrase?

Some phrases do not contain a subject, while others have both a subject and a verb.

Typically, you use a comma to distinguish the introductory words from the central part of the sentence.

Also, some introductory phrases are completely unnecessary, as the second half of the sentence is the main clause.

When touching up on your writing skills, it’s essential to understand when to use a comma after an introductory phrase, what complete clauses are, and how to form a grammatically correct statement.

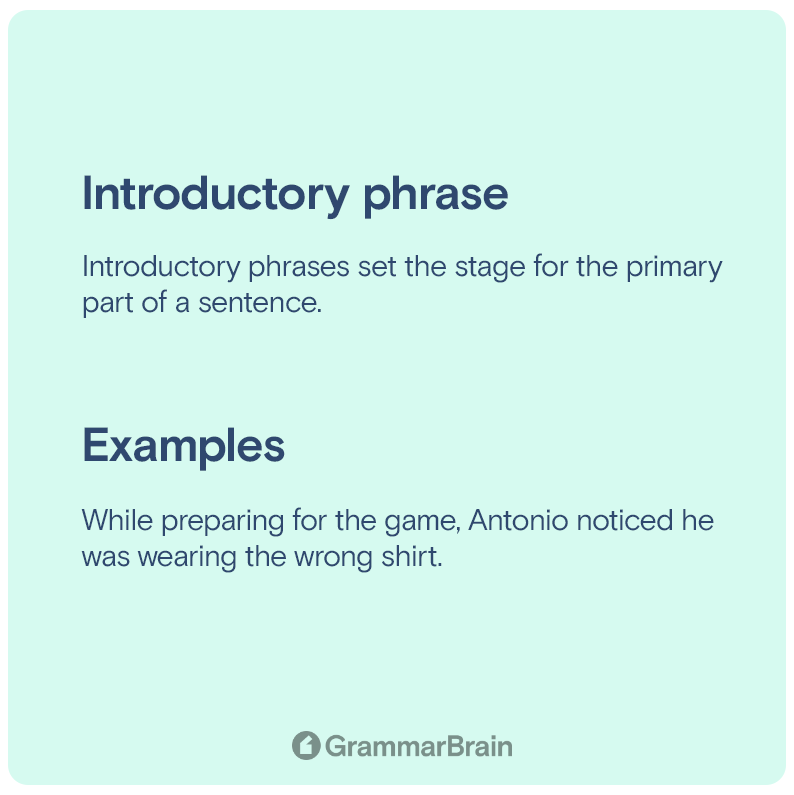

Introductory phrases set the stage for the primary part of a sentence.

With that, these phrases don’t have their own subject and verb.

Instead, they rely on the subject and verb in the main clause.

When using introductory phrases, you are telling the audience that the very beginning of the statement is building up to the central message that is yet to come.

For instance, “While preparing for the game, Antonio noticed he was wearing the wrong shirt.”

In this case, “While preparing for the game” acts as the introductory phrase, as you do not yet know what the main message of the statement is.

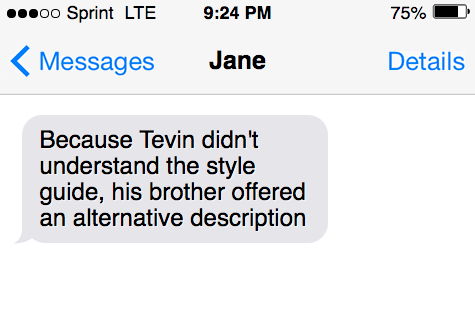

Also, keep in mind that introductory phrases are different from introductory clauses.

Put simply, yes, introductory clauses are slightly different from phrases.

With an introductory clause, the fragment of the sentence has a subject and a verb.

Essentially, these clauses are dependent clauses that usually appear at the start of a sentence.

However, they can be at the end of a statement, too, without changing its meaning.

When using an introductory clause, you use a comma to separate it from the independent statement.

In this case, you would not leave the introductory clause “As Tiffany was running across the parking lot” as its own sentence.

The sentence’s meaning relies on the independent phrase “she noticed her best friend from elementary school” to make sense.

An introductory participial phrase introduces the reader to the main clause of a sentence.

By doing so, it provides context to the introductory elements that help improve comprehension.

Further, these phrases are a type of verb phrase that can be short, like fewer than five words, or longer, like more than four words.

Also, these introductory dependent clauses may or may not include direct objects.

As you can see, “having eaten ten ice cream sandwiches” isn’t a complete thought.

Therefore, there is a comma after an introductory phrase like this to prepare the audience for the rest of the sentence.

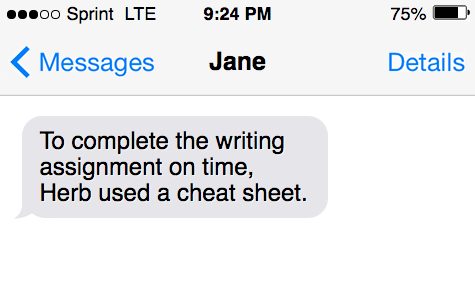

An infinitive introductory phrase is any clause with an infinitive verb plus any modifiers to complements.

That said, the complement of an infinitive verb will often be its direct object, while the modifier will typically be an adverb.

For instance, “Stacy likes to write the words slowly,” sees “to write” as the infinitive action word, “the words” as the complementing direct object, and “slowly” as the modifying adverb.

The entire bolded text makes up an infinitive phrase.

By itself, an infinitive introductory phrase cannot act as a complete sentence, as it relies on the second half of the statement to provide context.

Typically, these introductory phrases begin with “to” or “in order to.”

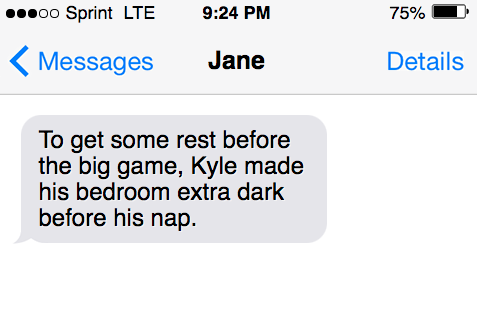

Here are some types of introductory phrases using infinitive qualities.

As you will notice, there is typically a comma after an introductory infinitive phrase.

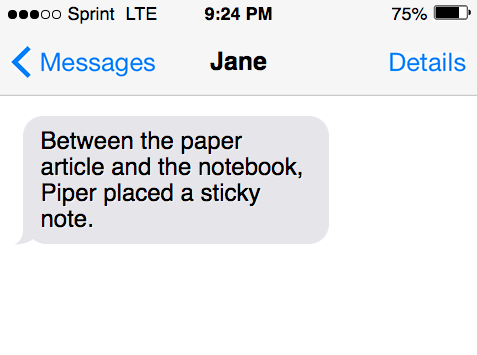

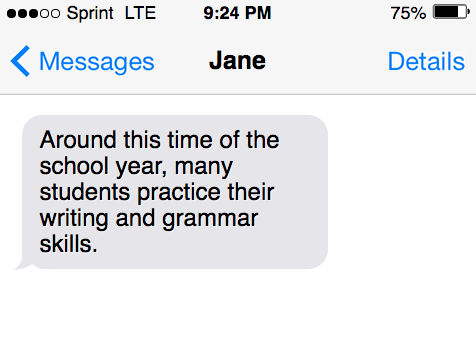

One example of an introductory phrase is an introductory prepositional phrase.

These phrases are placed at the beginning of a statement and act as a dependent clause.

That said, dependent clauses cannot serve as complete sentences on their own because they do not include their own subject.

One instance where you may use an introductory prepositional phrase includes the following statement:

“Around this time of year, many students struggle managing their school work with their social life.”

Prepositional phrases like, “around this time of year” are dependent because they cannot be complete sentences on their own.

However, the independent phrase “many students struggle managing their school work with their social life” can undoubtedly serve as a complete sentence on its own.

This type of introductory phrase can sometimes have two prepositional phrases in the dependent clause.

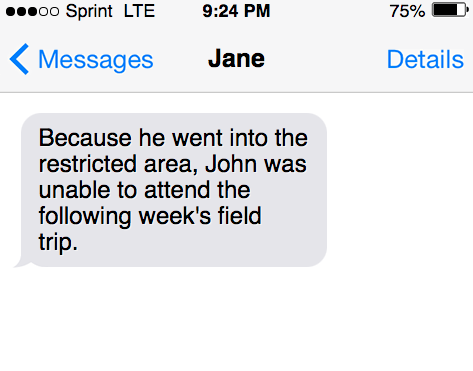

For instance, “Because he went into the restricted area, John was unable to attend the following week’s field trip.”

In the previous statement, the two prepositional phrases are “because” and “into.”

The below examples are an introductory phrase with a prepositional phrase:

An introductory phrase with an absolute phrase can be tricky to identify.

Absolute phrases do not attach themselves with a conjunction.

Instead, all that’s needed to separate them is a comma.

Typically, these phrases only consist of a noun and a modifer.

Introductory absolute phrases explain a “cause for” or a “condition of” something.

When reading a sentence like this, the reader would make a distinct pause after reaching the comma.

An appositive phrase follows a noun or noun phrase in apposition to it.

That said, these phrases offer additional information that further identifies or defines it.

Put simply, an appositive phrase is bonus information in a statement.

For instance, “Caleb Brown, a student at Purdue, is quite accomplished at math,” observes “a student at Purdue” as the appositive noun phrase.

Appositive phrases can be either restrictive or nonrestictive depending on the sentence.

Restrictive appositive phrases include a noun that is necessary for the reader to understand the sentence.

With restrictive appositive phrases you typically do not use a comma to separate the noun.

Take this case of a restrictive appositive phrase:

“Joey,” in this case, is the article that acts as the restrictive appositive phrase.

Overall, a restrictive appositive phrase acts as a way to include additional necessary information, providing context to the statement.

A nonrestrictive appositive phrase is the most common type of appositive phrases.

With that, a nonrestrictive appositive phrase can be left out of a sentence, and it will not change the meaning.

Typically, a nonrestrictive appositive sentence starts with the subject followed by a comma, then the additional information is sandwiched between another comma.

In this case, the information “a basketball coach” is extra, as the reader would have understood the statement without it.

When writing introductory prepositional phrases, you always use a comma to separate the dependent from the independent clause.

In the case of introductory infinitive phrases, you almost always use a comma after the introductory element.

An introductory phase with a participle always demands that you use a comma after the particple.

Inside this article

Fact checked:

Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.