On March 9, the House Ways and Means Committee and Energy and Commerce Committee passed the American Health Care Act, the Republican leadership’s plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In fact, the legislation would make changes beyond the ACA, including major changes in the Medicaid program, which provides health coverage for 1 in 5 Americans. The House bill would cap federal funding for the more than 74 million low-income children, adults, seniors, and people with disabilities covered by Medicaid. It would also phase out enhanced federal funding for the 11 million adults newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA Medicaid expansion.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the House bill would reduce federal spending by $1.2 trillion over the period 2017-2026 and reduce the federal deficit by $337 billion. The total reduction in federal spending over the 2017-2026 period includes a reduction of $880 billion in federal spending for Medicaid. The reduction in federal Medicaid spending would be used to help finance the tax credits and the federal revenue reductions attributable to repeal of the ACA taxes provided by the House bill. By 2026, 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid relative to the number expected under current law and number of uninsured people would increase by 21 million, reaching 52 million in 2026. This brief considers five key Medicaid implications of the House bill.

The 74 million individuals covered by the Medicaid program include many of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people in our society. Among those served by the program are millions of low-income pregnant women, infants, children, and parents and other adults – most of them in working families. Millions of poor senior citizens and millions of low-income Americans of all ages with physical disabilities, developmental disabilities, chronic conditions, and serious mental illness also rely on Medicaid. The individuals and families covered by Medicaid lack access to other affordable health insurance because of their low income or health needs. Without Medicaid, nearly all of them would be uninsured or underinsured for health and long-term care they need.

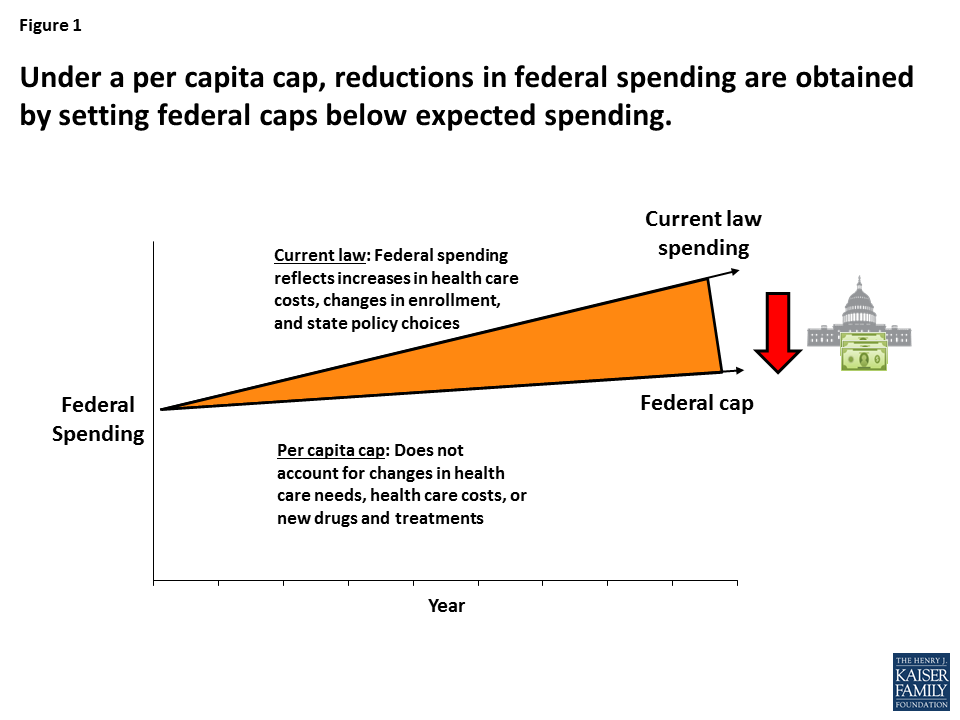

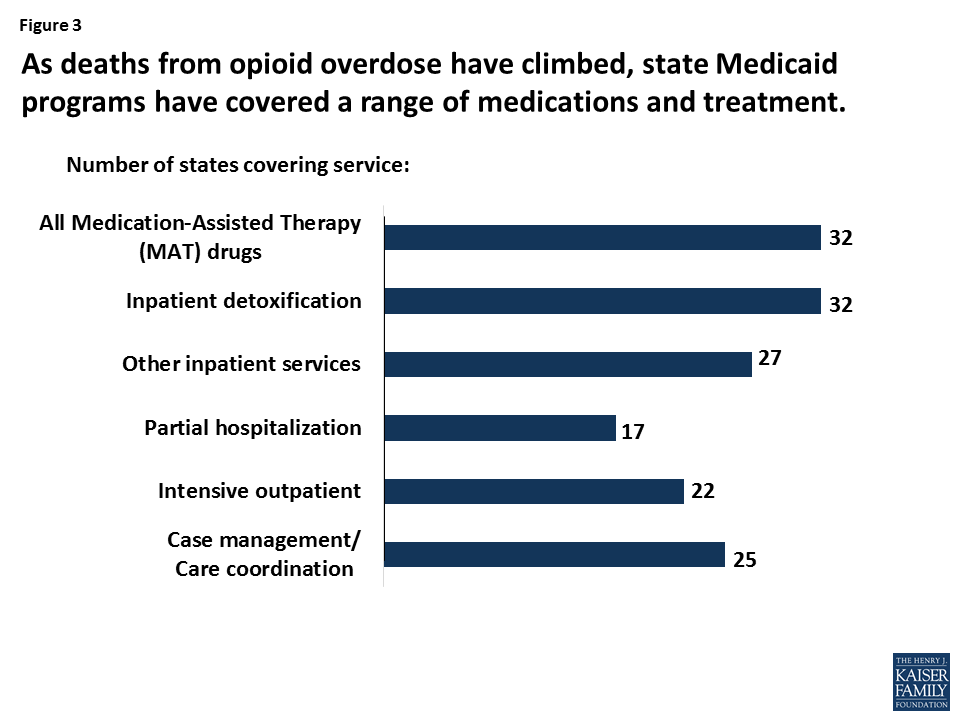

Throughout the Medicaid program’s history, Medicaid costs and risks have been shared by states and the federal government. The guarantee of federal Medicaid matching funds with no pre-set limit expands states’ capacity to provide health coverage for their residents and helps them manage increases in Medicaid costs that are fueled by health care cost inflation, the emergence of expensive new treatments and drugs, and the aging of the population. Because states share the costs of Medicaid, they have strong incentives to run efficient and effective programs, and state cost-cutting measures taken in hard economic times, including reductions in provider payment, have led to lean Medicaid operations. Beginning in FY 2020, the House bill would cap federal Medicaid funding per enrollee to achieve federal savings, shifting costs to states (Figure 1). According to the CBO, under the House bill, federal Medicaid spending would fall by $880 billion over the period 2017-2026. In 2026, federal spending for Medicaid would be about 25% lower than expected under current law, and 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid than expected under current law.

The bill would give states some flexibility to reduce costs by repealing the requirement that states provide the federally-defined essential health benefits for Medicaid expansion adults. However, it would also reduce states’ flexibility to maintain Medicaid eligibility and coverage at current levels.

Figure 1: Under a per capita cap, reductions in federal spending are obtained by setting federal caps below expected spending.

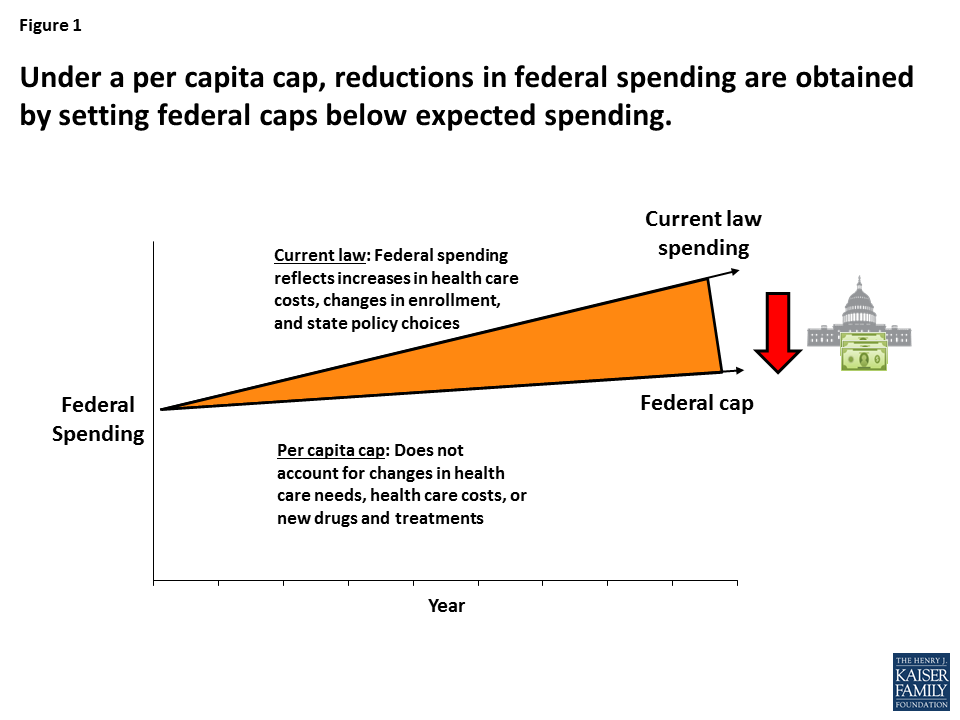

Medicaid spending per enrollee varies widely by state, by enrollment group, and over time (Figure 2). This variation stems from many factors, including demographic and health differences across states, variation in spending by enrollment group, local health care prices, and state Medicaid policy choices. The House bill would cap federal Medicaid funding per enrollee based on five groups: the elderly; individuals with disabilities; children; Medicaid expansion adults; and other adults. The federal per-enrollee caps would be based on states’ Medicaid expenditures in 2016, trended forward to 2019 by the medical CPI. Using a base year and a uniform index to establish the federal caps would lock states into their past Medicaid experience and omit consideration of substantial state variation in actual Medicaid per-enrollee spending growth. To illustrate, although Medicaid spending per child fell by 1.4% annually in Connecticut and grew by 13.3% annually in Arizona during the period 2000-2011, the federal cap per child would be determined in both states using the medical CPI, which is high compared to Connecticut’s actual experience and low compared to Arizona’s. This uniform approach would have differential impacts on states’ ability to address changing needs and new health challenges.

Figure 2: Average annual growth in Medicaid spending per enrollee varies widely by state and enrollment group, 2000-2011

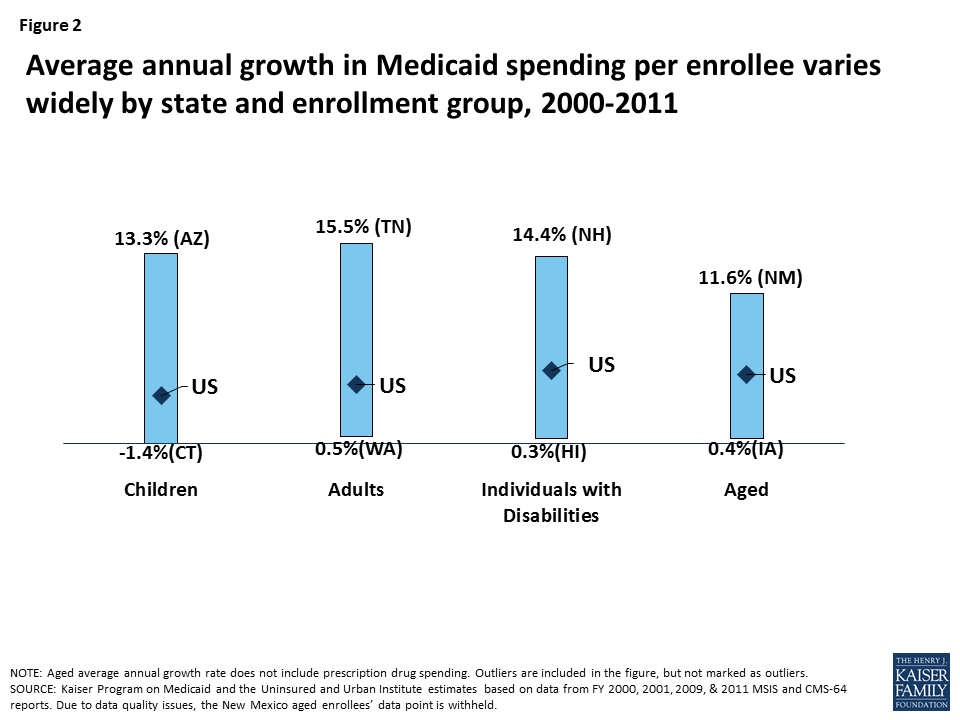

The availability of federal matching funds as needed helps states respond to changing coverage needs related to economic recessions; public health emergencies like HIV/AIDS and the opioid addiction epidemic; the growing numbers of the very old; disasters like 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina; and the emergence of new but costly treatments, like drugs for Hepatitis C (Figure 3). Converting to capped federal funding, as the House bill provides, would shift the risk for spending above the federal caps to states, increasing pressure on state budgets over time and likely leading to reduced coverage and access to care for low-income people, higher out-of-pocket costs, and increased uncompensated care costs for hospitals, clinics, doctors, nursing homes, and other providers.

Figure 3: As deaths from opioid overdose have climbed, state Medicaid programs have covered a range of medications and treatment.

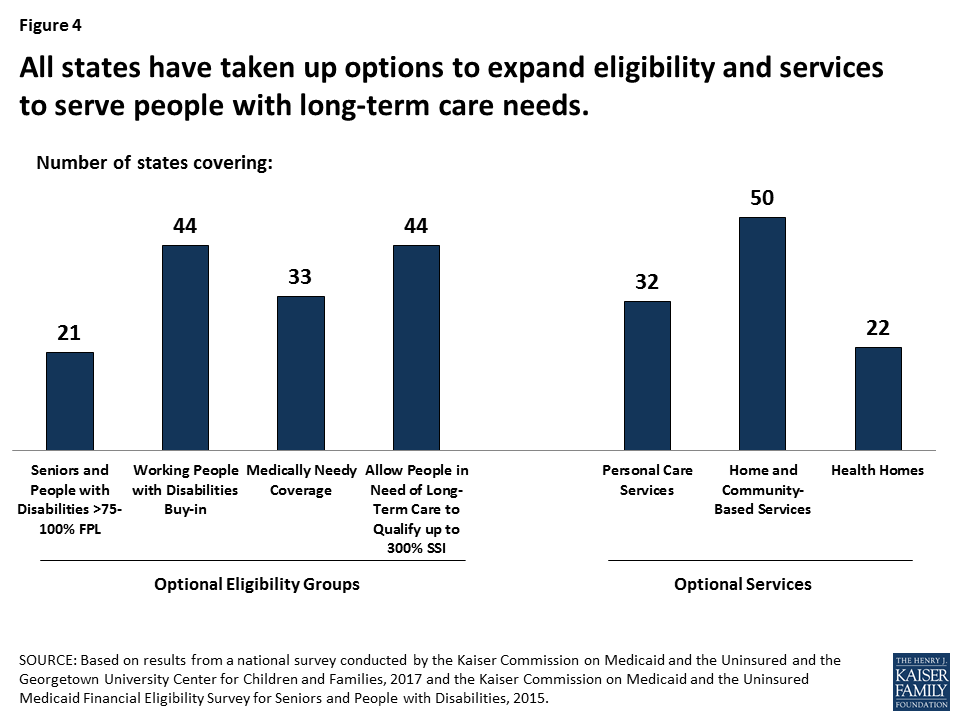

In addition to providing health insurance for poor families, Medicaid is the nation’s predominant source of financing for long-term care, serving 1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries and 2 in 5 people with disabilities. States have used their flexibility in Medicaid extensively to cover optional Medicaid groups and services to meet the long-term care needs of their residents, and a large share of their Medicaid spending is associated with these policy choices (Figure 4). Because of Medicaid, many people who would otherwise be in nursing homes are able to live independently and safely in the community. Under the House bill, states facing budget pressures might reconsider their optional expansions of Medicaid eligibility and services.

Figure 4: All states have taken up options to expand eligibility and services to serve people with long-term care needs.

Medicaid provides health coverage for people who are poor or who have substantial health care needs but cannot afford private insurance or need more extensive benefits than it provides. Federal and state expansions of Medicaid and CHIP for children have led to a sharp decline in the uninsured rate for children, which fell from 14% in 1997 to an historic low of 5% in 2016. Following passage of the ACA, the nation experienced an unprecedented decline in the uninsured rate for nonelderly individuals, from 16.6% in 2013 to an all-time low of 10% in 2016. The 32 states – including 16 states with Republican Governors – that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to adults led the declines.

With enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion, states have been able to provide coverage for millions of uninsured adults, including many with chronic physical and mental illnesses; the Medicaid expansion has also been instrumental to states’ ability to respond to the opioid addiction epidemic. The House bill would end the enhanced federal funding for the expansion population in 2020, which would place substantial budget pressures on states to maintain coverage, or lead the uninsured rate to climb if states are unable to shoulder these additional costs alone. CBO’s report on the House bill estimates that federal spending for Medicaid would drop by $880 billion over the 2017-2026 period due to capped federal Medicaid funding and the termination of enhanced federal funding for the Medicaid expansion. By 2026, an estimated 14 million fewer people would be covered by Medicaid relative to the number expected under current law, and number of uninsured people would rise to 52 million – an increase of 21 million over 2017.

Figure 5: In the 32 states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, 11 million newly eligible adults gained coverage.