The Second District Court of Appeal recently held that the corporate and individual owners of a residence for the disabled had a legal duty to prevent the sexual assault of one of its residents. The key to the court’s analysis was a detailed examination of the admissibility of police reports and the witness statements contained within. The court held police reports themselves are admissible under the official records exception. Although witness statements contained in police reports may be hearsay, the statements become admissible if offered a purpose other than the truth of the matter states such as to prove notice. Witness statements may also be admissible under a recognized hearsay exception such as admission of a party opponent.

Plaintiff Jane Doe (“Doe”), who was in her 20s but had the mental age of a child, was sexually assaulted at the Brightstar residence for the disabled.[ii] Doe could not do things for herself and required close supervision. Doe was sexually assaulted by a handyman who was classified as an independent contractor.[iii] The handyman was instructed to have no contact with the residents, to not wander from his work area, and to never be alone with a resident.[iv]

On the night in question, a nighttime caregiver found the handyman in the backyard of the residence with Doe. The nighttime caregiver saw Doe undressed from the waist down and saw the handyman adjusting his pants and zipper.[v] The handyman fled the scene and later fled the country.[vi] Brightstar did not have surveillance cameras or an alarm system on the property and had only one caregiver on duty that night.[vii]

Doe sued Brightstar and its individual owners for negligence; negligent hiring/retention; and negligent failure to warn, train, or educate. Brightstar and owners moved for summary judgment claiming they had no duty to prevent the assault because it was not foreseeable. After ruling the statements contained in police records were inadmissible hearsay, the trial court granted summary judgment because there was no evidence defendants had notice of the handyman’s dangerous propensities.[viii] Doe appealed.

Doe’s appeal raised two central issues: (1) whether the police reports were properly excluded as inadmissible hearsay and (2) what duty defendants owed Doe.[ix]

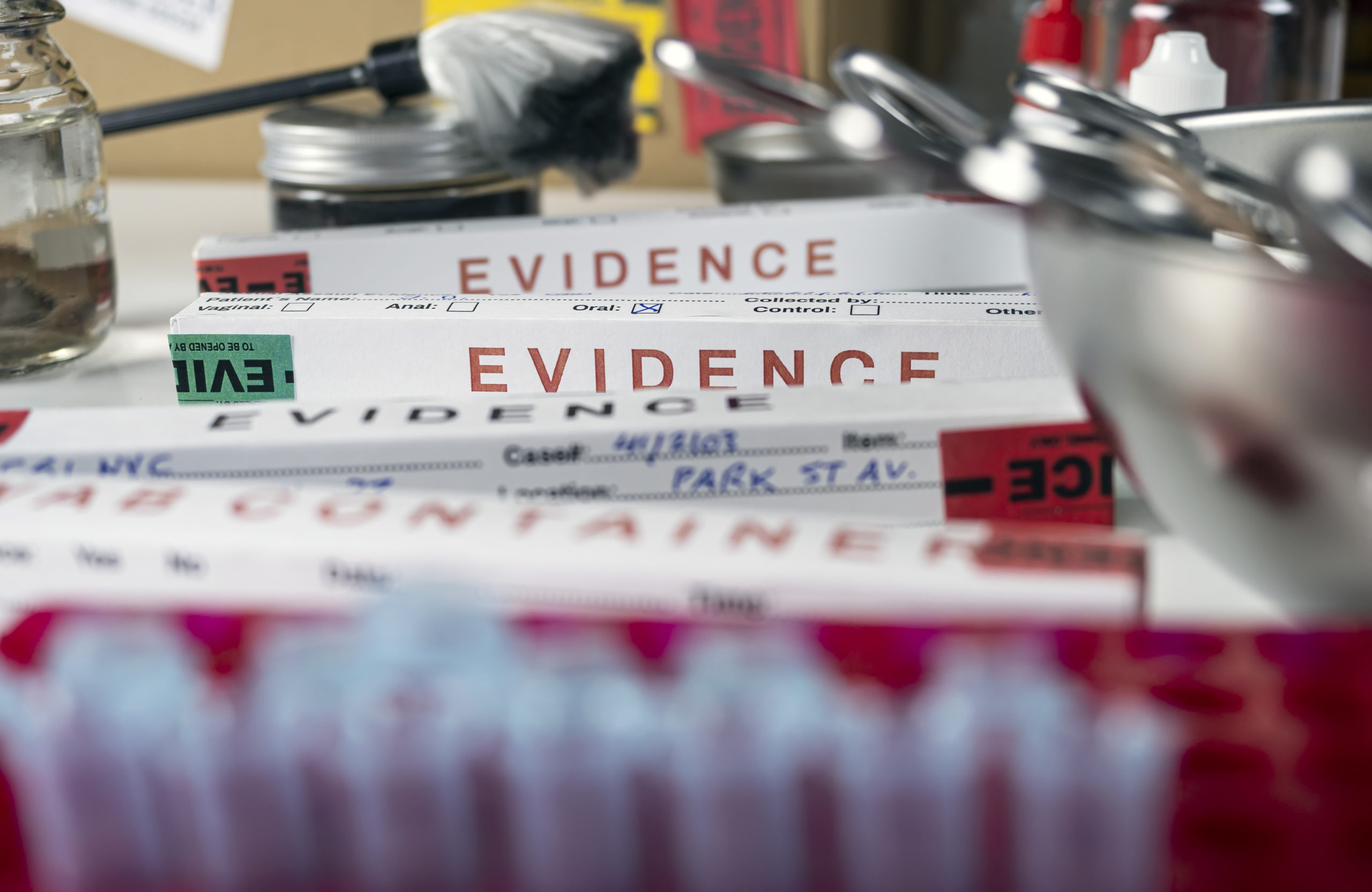

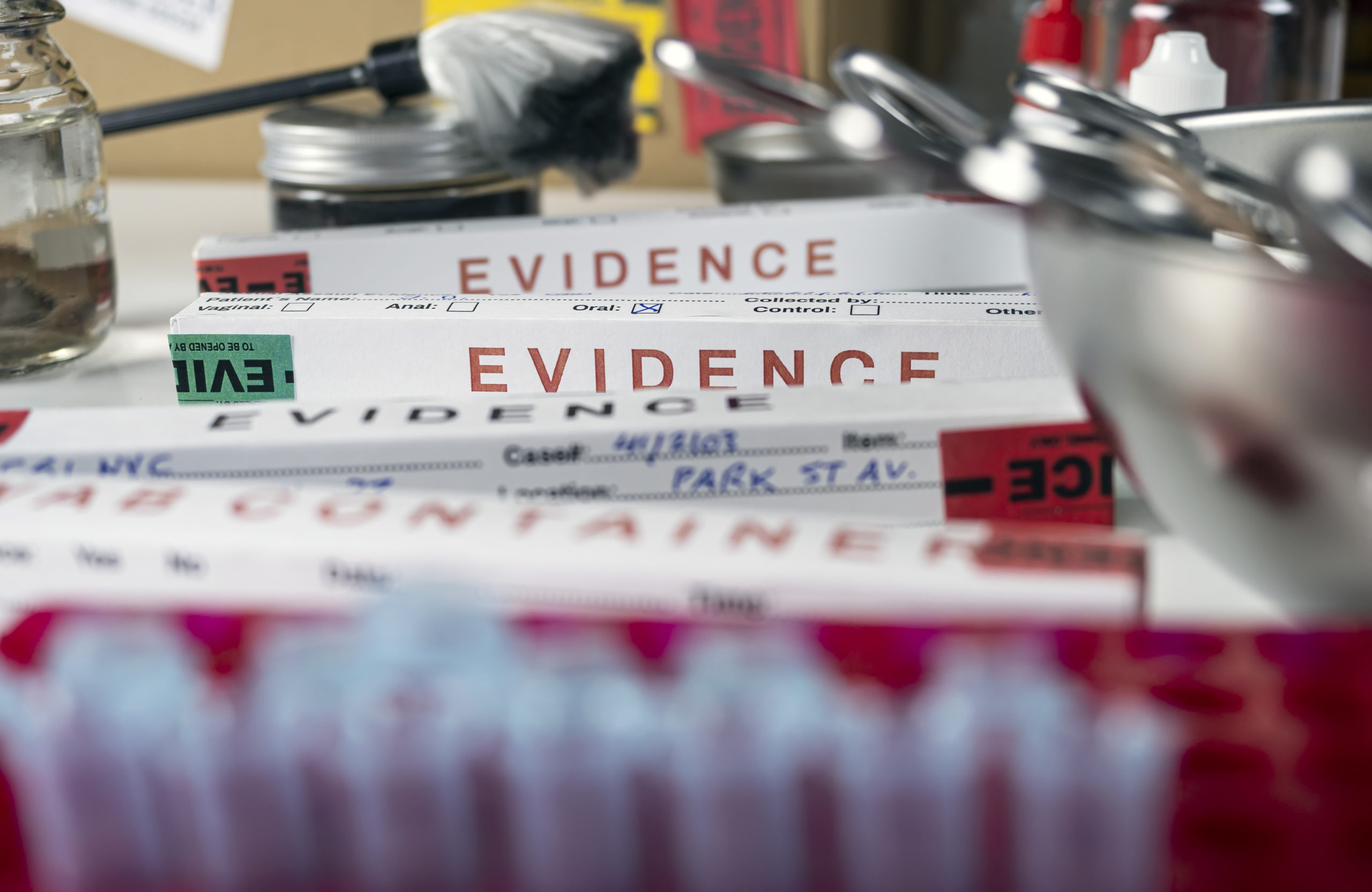

a. Police Report Evidence

The trial court excluded evidence from the police file showing the owners knew the handyman had a history of harassing women.[x] There were two categories of police file evidence excluded as inadmissible hearsay. The first category of evidence included statements made to the police by one of the owners. The owner told the police shortly after the incident that he knew the handyman had a “history of loitering around the facility and harassing female employees.”[xi]

Police reports are inadmissible when they contain improper multiple hearsay.[xii] However, double hearsay is admissible if the evidence rebuts the hearsay objection at each level.[xiii] The court analyzed the first level of hearsay namely the owner’s statement to the police.[xiv] The court found the owner’s statement was admissible under the hearsay exception allowing the admission of a party opponent.[xv] The second level of hearsay is the police report itself which was admissible under the official records exception to the hearsay rule, which presumes public servants act with care and without bias or corruption.[xvi]

The second category of police file evidence included statements made to the police by Brightstar employees.[xvii] These statements described observed intimacy between Doe and the handyman and, as reported in the police report, were triple hearsay.[xviii] However, the court explained these statements were not in fact hearsay because they were not being offered by Doe for the truth of the matters stated but instead, were being offered to impute knowledge from the employee to the company, thereby establishing notice.[xix] These statements established the employee and therefore the company and owners had knowledge the handyman was on the property late at night and knew Doe called the handyman “daddy.”[xx]

The court held the exclusion of this evidence was an abuse of discretion.[xxi] This evidence created an inference the defendants had notice the handyman was loitering to groom a disabled woman for assault, which went to the issue foreseeability.[xxii] Further, the evidence would have allowed the trier of fact to infer the handyman was a “problem waiting to happen.”[xxiii] Because one of the owners submitted a declaration in support of the summary judgment stating he had no basis for suspecting the handyman had the propensity to harass women, the trier of fact had to resolve the conflicting evidence.[xxiv]

b. Duty

The court introduced its analysis of duty by framing the issue in terms of Brightstar’s duty to prevent third-party criminal conduct.[xxv] In this case, the defendants’ duty was to take cost-effective measures to protect Doe from foreseeable harm from the handyman.[xxvi] The court noted defendants and Doe were in a special relationship creating a legal right to expect protection from a defendant who can control a dangerous third party’s conduct.[xxvii] Defendants had the ability to control when and under what conditions the handyman worked and also the ability to replace him at will.[xxviii] The court also found an analysis of the factors set out in Rowland v. Christian favors a finding defendants owed a duty to Doe.[xxix] Having found duty, a factual dispute exists as to whether keeping the handyman at Brightstar was a breach of duty causing Doe’s injuries.[xxx]

Property owners should consult with an attorney when there is an injury on property which is caused by third party criminal activity before giving statements to the police. Here, the owner made a party admission to the police which directly contradicted the owner’s sworn declaration submitted to the court in support of the summary judgment motion. The court’s analysis of the hearsay rule and its exceptions as applied to police report evidence is very instructive for attorneys considering how often the admissibility of police reports and the statements contained within are an issue in civil as well as criminal matters.

[i] Doe v. Brightstar Residential Incorporated et. al. Case No. B304084.

[ii]Doe v. Brightstar Residential et. al., p. 2